A display of enamel pins by local artist @bachoochi available for sale at Makers Guildford. Several of the pins feature characters from Genshin Impact.

For my final project I wanted to explore the legal question of fan-made merchandise of popular intellectual properties. As someone who is an avid supporter of small businesses (read: has bought a truly excessive amount of stickers), I’ve always wondered about the legality of some of the products sold. Aside from original art, many small artists also sell fan art as stickers, keychains, prints, etc. for commercial profit at markets or conventions, with some artists even making a living out of doing so. These days fan-made merchandise (“merch” for short) is fairly common to see, particularly with popular IPs.

In Canada, fan art, as a derivative work not created by the copyright owner, is prima facie copyright infringement. As well, fan art that has been turned into merch does not fall into one of the 8 fair dealing categories enumerated in the Copyright Act, presumably exempting it from that defense. Furthermore, the inherently commercial nature of merchandise means that s. 29.21(1) doesn’t apply, since this provision only covers content done solely for non-commercial purposes. Despite this, fan merch is prevalent. It appears to exist in a sort of gray area where its continued existence stems from most copyright holders turning a blind eye, whether that is due to the impracticality of cracking down on every single creator, implicit approval of fan merch, or other reasons. The prevalence of fan merch will also depend on the copyright holder and how protective they are of their IP.

Fan merch has become an accepted, and even expected part of fan culture, to the point where there is beginning to be explicit support of its existence. Some copyright holders have begun setting out “fan merch policies”, providing guidelines on what types of merchandise fans can or can’t create. The policies set out a list of rules where, if complied with, the copyright holder promises not take any action, legal or otherwise, essentially giving creators license to create fan merch within limits. Interestingly enough, all the policies I could find were from video game companies. I feel like there’s a joke I can make here about modding, but fan creations might be a more intuitive part of the culture surrounding gaming, as opposed to movies or tv shows. Or it may have something to do with many video game developers with merch policies being, or starting as, smaller-sized indie companies, with much less official merchandise to compete with, reduced capacity to enforce copyright, and perhaps a greater appreciation of their fanbase. As well, many of the companies who have published such policies are based in the U.S., where the concept of fair use exists (in contrast to a jurisdiction like Japan, where there is no equiavlent concept). Whatever the reason for the specificity, the developers behind games such as Hades, Genshin Impact, Runescape, Hollow Knight, Undertale, Among Us, and more, have all published policies online around the selling of fan merch.

The policies are a way for the studios to explicitly recognize the passion and enthusiasm of fans that drives them to create merch in the first place, while at the same time being able to minimize any detrimental effects on the original copyright owner. Indeed, if the fan merch is not resulting in any adverse effects, it seems counterintuitive for a company to punish the fans who love their IP enough to create for it. Reading through the different policies, commonalities among most include prohibitions on:

- Mass distribution. Some policies give specific numerical caps on how many products can be sold, ranging from 100–500 units.

- Using any official trademarks or logos.

- Listing the merch on large “print on demand”/mass distribution stores, for example Redbubble, Displate, Society6, or Amazon. This also translates into a requirement that the merchandise be sold directly to consumers, whether in person or through a personally-managed online shop.

- Using official art or source materials. This means a requirement that the art on the merch itself be an original creation. Related to this, there is also general prohibition on fan merchandise that competes with official merchandise in some way, meaning that the fan merch cannot be too similar to any merch put out by the company or its authorized licensees.

- Kickstarter campaigns or crowdfunding the creation of the fan merch.

- Using the IP in a manner that harms the company’s reputation or “runs counter to the spirit” of their games.

- This includes selling anything with offensive or inappropriate content. (As a side note, my personal favourite provision is the one from Innersloth which explicitly prohibits “us[ing] the Among Us IP to depict religious or political imagery…includ[ing] depictions of religious or political figures, emblems, logos, or any other associated iconography.” Only the Among Us policy has this specific requirement, which I feel tells a story in itself.)

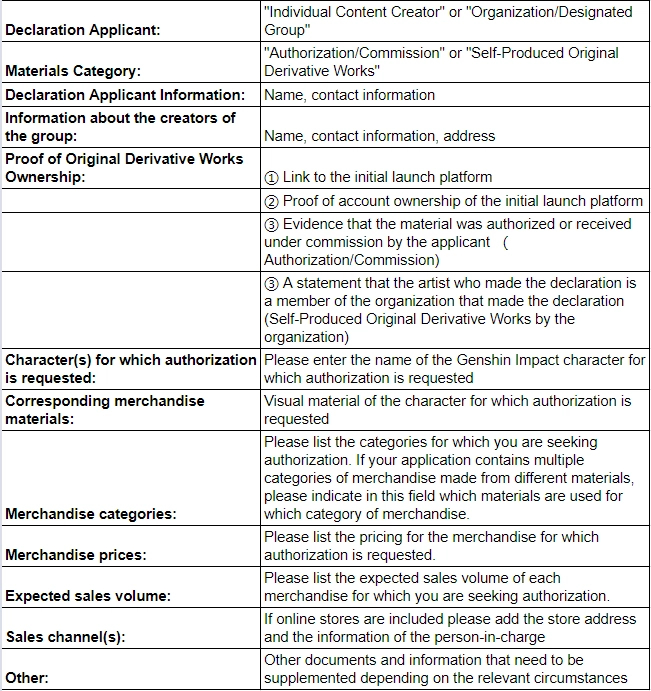

Mihoyo’s sample declaration form, from their website

- This includes selling anything with offensive or inappropriate content. (As a side note, my personal favourite provision is the one from Innersloth which explicitly prohibits “us[ing] the Among Us IP to depict religious or political imagery…includ[ing] depictions of religious or political figures, emblems, logos, or any other associated iconography.” Only the Among Us policy has this specific requirement, which I feel tells a story in itself.)

The most comprehensive merch policy by far is that of Mihoyo, the studio behind the popular gacha role-playing games Genshin Impact and Honkai Star Rail. Their policy includes not just a list of guidelines surrounding the production of “light hobby merchandise”, but provides for an application process for the authorization of certain categories of merchandise. For example, if the quantity of a product made by an individual “exceeds 500 units, an application for prior authorization through official channels is required.” This requires the creator to fill out a declaration form with their contact information and information about the merchandise they plan to sell.

While these policies are not legal rules in themselves, I thought it was interesting how they essentially serve to create a quasi-legal regime that helps clarify the legal status of fan merch (at least with certain IPs), while at the same time balancing both creators’ and users’ rights. As well, the policies help to provide certainty to creators, as they no longer have to fear any legal repercussions from selling fan merch of those IPs, provided they follow the rules. I am also personally supportive of the recognition and appreciation of fan culture and fan enthusiasm. While such policies currently seem to be limited to video games, I am curious as to whether the practice will be adopted by other industries.

Copyright & Social Media

Copyright & Social Media Communications Law

Communications Law

Hi Celine,

Thank you for the post. As a Genshin player myself, I also find Hoyoverse’s rules super interesting, especially the way they set different categories with different threshold of infringement. I am very curious about “light hobby merchandise products”, which apparently include self-published print works, cotton dolls, dango, and cushions. They did not define the term, but instead just mentioned a few examples in the Q&A. I wonder if Hoyoverse created the rules on their own or learnt from other companies.

On a related note, I am glad to see that Chinese companies like Hoyoverse is being proactive about IP protection. It was probably less than 10 years ago when counterfeit products are easily accessible without any regards to IP. China came a long way from acquiescing that to empowering companies to regulate “light hobby merchandise” products. The IP law protection in the PRC started late and is still behind most industrialized countries, but it is growing very fast. Such a growth results partly from the pressure from conforming with international trade law and WTO rule, partly from the increasing demand of IP protection by tech companies like Hoyoverse. China also take anti-monopoly very seriously. I guess it may have the advantage of being a latecomer so they can start from learning good practices from other countries. Given China’s status in the global supply chain, I am very curious about how it interacts with other countries in the international law on IP, whether it will start to participate in the rule-making, and how it will impact the international norm of IP protection.