For my project, I chose to look into the implications and issues surrounding intellectual property protection regarding makeup dupes. With the prices of luxury goods remaining high despite growing economic pressures, dupes are becoming increasingly popular. This trend falls in line with the so-called “lipstick index” which suggests cosmetics sales remain steady, or even rise, during recession periods as shoppers substitute higher-ticket items for lipsticks and other smaller goods. [1] If dupe companies successfully replicate an expensive product at a lower price, it could have substantial market ramifications. Makeup dupes are changing the ways consumers purchase makeup products, and the prevalence of these cheaper alternatives brings a range of intellectual property implications to consider within trademark and patent law.

What are Dupes?

Short for duplicate, the term dupe describes a product which intends to resemble a high-end product at a lower price point, often with similar packaging, appearance, or formula.[2] Unlike counterfeits, most dupes do not attempt to trick the consumer into thinking they are buying the original high-end goods. Counterfeit products, however, copy the original brands’ registered trademarks.[3] Therefore, counterfeit products are identical to a high-end brand product for the purpose of deception and belief of their authenticity, while a dupe aims to help the consumer affordably acquire a good.

Types of Dupes

1. Packaging and Product Design Dupes

Packaging and product design imitations are the most common form of makeup dupe. A product is crafted to mimic the visual aesthetic of the higher-end product, often replicating elements like external packaging or the design and colour scheme of the product itself. These dupes primarily aim to evoke the style and appearance of the original product, rather than replicate its effects or formula (though this may also be attempted). Essentially, they seek to evoke the essence of the original without claiming to be identical. Notorious “duper” brand e.l.f Cosmetics exemplifies this type of dupe:

Trademark Law in Packaging and Product Design Dupes

Trademarks are the main form of intellectual property protection for beauty brands. A “brand” can encompass many things, but it usually includes the company’s name, logos, packaging, and product names, all which form the appearance of the product itself and which could receive trademark protection individually. However, trademark protection is not a sufficient solution to prevent product dupes from occurring. There are two reasons for this: First, elements of the original makeup product packaging required to effectively prevent copying may not be registrable. Second, supposing the product can be sufficiently trademarked, there would not be a likelihood of confusion.

I. Unregistrability

Section 12(2) of the Trademarks Act prohibits registration of a trademark if the features are dictated primarily by a utilitarian function.[4] Section 20(1.2) further limits any protection given by allowing use of any utilitarian feature contained within a trademark.[5] A trademark’s features are dictated primarily by a utilitarian function if those features are essential to the use or purpose of the goods.[6] The product design of makeup items are often integral to the use of the product itself. For example, a type of lip gloss applicator may not receive protection as the applicator may be functionally necessary to the use of the lip gloss. Trademark law is focused on source-identification rather than preventing competitive use.

A further factor contributing to the unregistrability of packing and product design is non-distinctiveness. For an application for the registration of a trademark not to be refused, the trademark must have some degree of inherent distinctiveness or must have acquired distinctiveness at the time of filing of the application.[7] Product design or packaging may be considered inherently distinctive when nothing about it refers the consumer to more than one source.[8] Within the beauty industry, product design often serves purposes beyond source identification (as outlined above) and would typically not be inherently distinctive. There are a finite number of ways to contain certain makeup products to ensure functionality, necessarily meaning that multiple brands will use similar product designs. A product design or packaging, absent sufficiently novel or unique elements, is thus likely to be unregistrable.

ii. No Likelihood of Confusion

If elements of a makeup product design or packaging were sufficiently registrable, enforcement of the accompanying rights may require establishing confusion between the registered product and the dupe.[9] With the rise in popularity of dupes, consumers may have become more attuned to original products as compared to cheaper alternatives. Accordingly, it may be difficult for brand owners to meet the test for consumer confusion. Most consumers in this context know they are purchasing a dupe instead of the original product as that is the purpose of a dupe. Consequently, there is typically no likelihood of confusion and thus no trademark infringement.

Of note is the concept of initial interest confusion. Initial interest confusion occurs when there is use of another’s trademark in a manner “calculated to capture initial consumer attention even though no actual sale is completed as a result of the confusion”.[10] Though this concept has not been adopted within Canadian courts, it aptly describes the only type of confusion that may bring dupes within infringement territory. Should this category of confusion be accepted within Canadian courts, the landscape of trademark infringement related to dupes could be drastically expanded.

iii. Depreciation of Goodwill

Lastly within trademark consideration of dupes is the possibility for infringement by depreciating the value of goodwill.[11] On the face of this infringement category, no confusion is required and leaves open the possibility of finding infringements by dupe products. In 2017, a high-end brand, Tatcha, filed a lawsuit against another high-end brand, Too Faced, alleging that Too Faced used nearly identical and inherently distinctive lipstick tubes which had caused harm to their goodwill.[12] Ultimately, this complaint was voluntarily dismissed. However, a high-end brand alleging depreciation by another high-end brand brings with it an implication that bringing forth a successful infringement claim against a cheaper, and possibly lower quality, product may be plausible. Despite this, mere association is not sufficient to establish depreciation.[13] The “piracy paradox” also tells us that lower-quality copies signal the status of the original, thereby increasing its relative value.[14] Dupes of high-end makeup may paradoxically benefit those original brands by inducing higher turnover of new products and additional revenue.[15] Depreciation of goodwill may be difficult to establish if the positional value of makeup as status goods is considered within the analysis.

2. Formulation Dupes

Similar to product design dupes, formulation dupes occur when brands attempt to emulate the specific effect or unique texture of a product. Below are two examples.

The Milk Makeup website describes their product as “a blush and lip stain with hydrating, bouncy jelly texture” while dupe brand EelHope describes theirs as a “moisturizing, elastic jelly texture that creates a transparent, buildable color effect after application”.

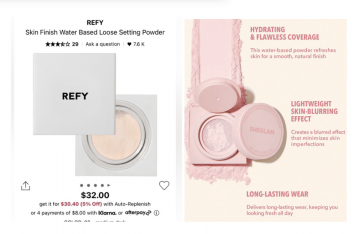

High-end brand Refy describes their product on their website as a “water-based powder that leaves your skin looking like skin” while cheaper alternative brand Sheglam states their “water-based setting powder leaves your skin looking natural and fresh all day”.

Patent Law in Formulation Dupes

Makeup formulations may be eligible for patent protection where they are new and sufficiently innovative.[16] However, patents may not be much more of a viable way to prevent beauty dupes as beauty products often do not meet the novelty or non-obviousness requirements. There are a finite number of ingredients that may used in beauty products, further shortened by restrictions imposed by the Food and Drugs Act and the Cosmetic Regulations

(See the Government of Canada’s Cosmetic Ingredient Hotlist: Prohibited and Restricted Ingredients for a list of prohibited and restricted ingredients

https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/consumer-product-safety/cosmetics/cosmetic-ingredient-hotlist-prohibited-restricted-ingredients/hotlist.html). As cosmetics have been used throughout history, with particular commercial growth in the 1800s, many of the same formulations will have already been invented and disclosed.[17] In this scenario, the frequently utilized ingredients and colours are deemed “predictable choices,” as many cosmetics companies rely on a shared pool of ingredients, therefore not satisfying the non-obvious or novelty requirements.

A further consideration regarding the viability of patent protection against dupes is the timeline of applying and being granted a patent. It often takes between three and five years post-application to acquire a patent, not including the time spent inventing the product.[18] In contrast to this, beauty trends undergo rapid changes. While traditionally these trends lasted for five to ten years, nowadays they can fall out of favour within the year. [19] This pace underscores the incompatibility with the use of patents as a form of protection as trends will likely pass before a patent can be granted.

For brands that are being negatively affected by the dupe industry, it may feel that there are limited enforcement options available. However, the best perspective may be to view it as a compliment. Imitation is a form of flattery, regardless. With the demand for luxury goods on the rise alongside increasing living costs, dupes are likely here to stay. The crucial factor lies in vigilant monitoring, ensuring swift enforcement actions against dupes that overstep boundaries.

References

[1] Laura Rodini, “What Is the Lipstick Index? Which Stock Market Trends Does It Predict?” May 25, 2023, TheStreet, https://www.thestreet.com/dictionary/lipstick-index.

[2] Samantha Primeaux, “Makeup Dupes And Fair Use,” (2018) 67:3 American University Law at 893, http://digitalcommons.wcl.american.edu/aulr/vol67/iss3/5.

[3] Garry Breitkreuz, “Counterfeit Goods in Canada: A Threat to Public Safety. Report of the Standing Committee on Public Safety and National Security”, (2007) 39th Parliament, 1st Session at 2.

[4] Trademarks Act, R.S.C., 1985, c. T-13, S.12(2) [Trademarks Act]

[5] Trademarks Act, S.20(1.2)

[6] Canadian Intellectual Property Office, “Trademarks Manual”, (2019), Government of Canada, https://manuels-manuals.opic-cipo.gc.ca/w/ic/TM-en#!fragment//BQCwhgziBcwMYgK4DsDWszIQewE4BUBTADwBdoByCgSgBpltTCIBFRQ3AT0otokLC4EbDtyp8BQkAGU8pAELcASgFEAMioBqAQQByAYRW1SYAEbRS2ONWpA at 92-93.

[7] Trademarks Act, S. 32(1)(b).

[8] Compulife Software Inc. v Compuoffice Software Inc., 2001 FCT 559 (CanLII) at para 19

[9] Trademarks Act, Ss.6(2), 20(1).

[10] Brookfield Communications Inc. v. West Coast Entertainment Corp. (1999), 174 F.3d 1036, 1062 (9th Cir. 1999) at 1062

[11] Trademarks Act, S.22(1).

[12] Ian W. Gillies, “Tatcha v. Too Faced: What Shade is your Trade Dress?” August 25, 2017, Knobbe Martens, https://www.knobbe.com/news/2017/08/tatcha-v-too-faced-what-shade-your-trade-dress.

[13] Veuve Clicquot Ponsardin v Cliquot Boutiques Ltd., 2006 SCC 23, at para 43.

[14] Kal Raustiala and Christopher Jon Sprigman, “The Piracy Paradox: Innovation and Intellectual Property in Fashion Design,” (2006) 92:8 Virginia Law Review at 1720, https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=878401 [The Piracy Paradox].

[15] Ibid at 1722.

[16] Patent Act, R.S.C., 1985, c. P-4, S.2.

[17] Cosmetics Info, “A History of Cosmetics”, https://www.cosmeticsinfo.org/history-of-cosmetics/.

[18] BDC, “How to Get a Patent”, https://www.bdc.ca/en/articles-tools/business-strategy-planning/innovate/intellectual-property-how-patent-product#:~:text=%E2%80%9CEngaging%20in%20the%20patent%20process,years%20to%20get%20a%20patent.

[19] Kara McGrath, “How Beauty Trends Met Their End, December 1, 2023, Allure, https://www.allure.com/story/how-beauty-trends-met-their-end.

Copyright & Social Media

Copyright & Social Media Communications Law

Communications Law

This is such a cool topic to choose. I recently bought some elf lip dupes myself and was surprised by how similar the consistency was to the Charlotte Tilbury one! truly a dupe haha!

So I did some light reading. – Companies possessing trademarked brands might pursue legal action if they suspect another brand is producing a product that closely resembles theirs. Nonetheless, courts have ruled that such imitations can be permissible under fair use principles, as long as they don’t intentionally confuse customers. For instance, in the case of KP Permanent Makeup, Inc. v. Lasting Impression I, Inc., the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that for a plaintiff to prove infringement, they must demonstrate a likelihood of consumer confusion, placing the legal burden primarily on the trademark holder. Interesting indeed!