1. Introduction

This paper examines industrial design protection in Denmark and Canada, reviewing a case from each country involving infringement action against similar, but not identical designs.

2. Copyright protection of Industrial Designs in Denmark

The Danish Copyright Act

The Danish Copyright Act (in Danish Ophavsretsloven, LBK nr 1144 af 23/10/2014) provides protection for applied art in section 1(1):

[Translation]

“Anyone who creates a literary or artistic work has copyright in that work, including work expressed in writing or speech as a fictional or descriptive representation, musical or dramatic work, cinematographic or photographic work, work of fine art, architecture or applied art (…)” [Emphasis added].

Case BS-15944/2020-OLR (Christian Bitz v K H Würtz)

This case was first decided in the Danish Maritime and Commercial Court [DMCC] on March 2020. The decision was appealed to the Eastern High Court [Court] who came to the same conclusion as the DMCC.

All quotes have been translated from Danish.

Facts of the case

In 2003-2006, K H Würtz [Würtz] made ceramic dinnerware and was successful in selling it to trendy Danish restaurants, including Copenhagen’s ‘NOMA’. The dinnerware was handmade stoneware in dark colours. Würtz had used an old glazing technique making the dinnerware look speckled and frosted. One plate had a broad rim surrounding a smaller food-surface. In 2016 Christian Bitz [Bitz], a well-known nutritionist, visited Würtz’s workshop and bought several of Würtz’s products. Five months later, Würtz saw what to him looked like his products, advertised on Instagram by Bitz. Würtz complained and brought action for infringement to the DMCC claiming he (Würtz) had copyright in the dinnerware and that Bitz had copied and thereby infringed his copyright.

The relevant products (Würtz to the left and Bitz to the right in each picture)

Is there copyright in dinnerware?

Bitz claimed ‘no copyright’, claiming to have followed a trend in the market and suggesting the glazing technique used by Würtz was an old technique which anyone could start using.

The expert witness explained there had been a trend in the market towards the use of ‘speckled glaze’ but Würtz’s design clearly differed from other similar products (page 71), Würtz’s dinnerware was not part of a trend when the dinnerware was launched in 2003, approximately 10 years before the trend arose. According to the expert witness, Würtz created the trend (Ibid).

The Court found that the dinnerware enjoyed copyright protection. It “reflects Würtz’s personality and expresses his free and creative choices and the work can be identified in a sufficiently precise and objective way” (page 82). The individual products stand out as unique (Ibid).

However, the ‘glaze-expression’ on its own was not as such protected under the Danish Copyright Act because “it cannot be identified in such a sufficiently precise and objective way which – independent of the works – separates Würtz’s glaze from other glazes” (Ibid). This would not be an acceptable “idea-protection” and would be damaging for “the free competition” (page 53).

Has copyright been infringed?

The Court found that the characteristic traits in Würtz’s products (similar expression and image, the black, grey and grey-green colourscheme and the speckled and frosted glaze) were reflected in Bitz’s products to such extend that the two gave a non-expert the same “identity-experience” (page 83).

Bitz made some interesting arguments, explaining his plate was designed with a broad rim for nutritionist reasons. A big plate with a smaller food-surface would make the dinner portion look bigger, making people eat less (page 24). However, an email correspondence between F&H (Bitz’s business partner) and the factory producing the Bitz-products showed that Bitz and F&H deliberately aimed at imitating Würtz’s products (page 83).

Both courts found copyright in Würtz’s dinnerware, and found that copyright had been infringed.

3. Copyright protection of Industrial Designs in Canada

The Copyright Act and the Industrial Design Act

In Canada, the Copyright Act, RSC, c C-42 [Act] offers protection for “a design applied to a useful article” until a useful article is reproduced more than fifty (50) times cf. section 64(2) of the Act. Where the protection under the Act ends, the Industrial Design Act, RSC 1985, c 1-9 [ID Act] offers protection for industrial design but only if the design has been registered cf. section 9 of the ID Act.

‘Design or industrial design’ according to the definition in section 2 of the ID ACT means “features of shape, configuration, pattern or ornament and any combination of those features that, in a finished article, appeal to and are judged solely by the eye; (dessin).”

Bodum USA, Inc v Trudeau Corporation (1889) Inc, 2012 FC 1128 [Bodum]

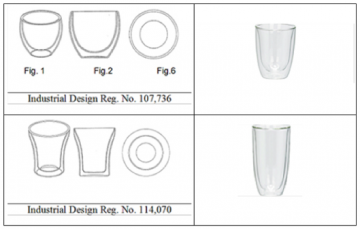

This case involves double-wall drinking glasses. PI Design AG and Bodum USA, Inc (the plaintiffs) alleged double-wall drinking glasses made by Trudeau since 2006 infringed the plaintiffs’ industrial registered designs (numbers 107,736 and 114,070) and sought relief under the ID Act. Trudeau sought a declaration that the industrial designs in question were and had always been invalid (para 3).

The relevant products (Bodum’s registered industrial designs on the left and Trudeau’s glasses on the right)

Was there infringement of the registered industrial designs?

Of particular relevance was the configuration of the double-wall glasses (para 47), the Court thereby ignored the utilitarian function of the double-wall glasses (para 51) i.e. the space between the walls which function was to e.g. keep the drink hot or cold.

First, the Court reviewed the prior art, finding it demonstrated that double-wall glasses and the lines of Bodum’s designs existed prior to 2003/2004 when Bodum introduced its double-wall glasses on the Canadian market (paras 59 and 82). An industrial design must be substantially different from prior art to be registrable (para 96).

Next, the Court reviewed the Legal Test for Comparison[1], and stated in para 71 that infringement would occur if Trudeau’s glasses “do not differ substantially from the (registered) industrial designs (…)”[“registered” added]. The Court concluded in para 90 that Trudeau’s glasses had almost no features of the configuration of Bodum’s registered industrial designs. The proportions and ‘lines’ i.e. the exterior curves and openings differed (para 83). As a result, the Court dismissed the plaintiffs’ infringement action[2].

4. Conclusion

Regardless if you agree that protection for industrial design should be available only for registered designs, the most distinctive difference is that industrial design in Denmark is protected under the Danish Copyright Act regardless of quantity. However, both Danish and Canadian courts will look at similar factors when assessing infringement, most notably if the alleged infringing design substantially differs from the ‘protected’ design and will not protect the intentional copier.

–

[1] The case was decided before the 2018 amendment of the ID Act, however the wording of section 11 defining infringement of an industrial design remains the same after the amendment.

[2] The Court also found that Bodum’s industrial designs did not meet the criteria entitling them to registration (para 99).

Copyright & Social Media

Copyright & Social Media Communications Law

Communications Law