Hi everyone!

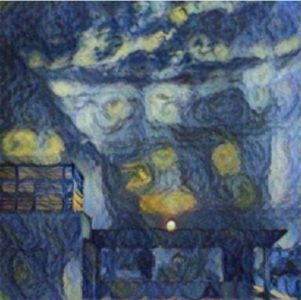

I want to elaborate more on the grant of copyright protection to an AI-generated work in the light of the Canadian Intellectual Property Office’s (“CIPO”) decision we mentioned during our classes. The registered work is Suryast painting below.

Photo Credits: Sukanya Sarkar (ManagingIP.com)

Photo Credits: Sukanya Sarkar (ManagingIP.com)

The co-authors identified are Raghav Artificial Intelligence Painting App and Ankit Sahni. Beforehand, the Indian Copyright Office has already registered this work, and the CIPO published it based on that registration. You can find the details of the registration here.

The essential dilemma of the decision is the objection of the CIPO to the DABUS patent applications on the grounds that it does not appear possible for a machine to have rights under Canadian law. The details of the patent application can be found here. On the other hand, the registration made before the Indian Office might be decisive. Nevertheless, could Canadian patent and copyright laws still be dissociated as such?

First, instead of who the author is, the question of what the author is was answered for the first time in copyright law’s history of 300 years. The grant of co-authorship to Sahni facilitates the assessment of several questions on this issue yet creates some problems in practice that I will address.

Which purpose of copyright law does this registration fulfill?

The public interest in AI-generated works’ encouragement was promoted with this registration; meanwhile, a just reward was provided for Sahni, both as author and user of the system. However, the dissemination of AI-generated works might be decelerated by the proliferation of monopolies granted to such works.

This registration is one of the possibilities that the connector model in copyright law has provided. Otherwise, the identification of an AI as a co-author will not fit into the concept of a romantic author, whose creativity is an extension of her identity and uniquely personal treat. We should note that even in France, where the notion of droit d’auteur emerges, moral rights are strongly protected and which is relatively an author-centric system, an AI has been registered as a composer in today’s circumstances.[1]

Is this work original?

The exercise of skill and judgment required by Justice McLachlin’s test is also up for debate, and it is unclear how the Office carried out this assessment. However, at this point, Sahni’s presence provides a preliminary clarification. Since AI systems can produce multiple works in mass, Sahni’s selection and interpretation of this painting may pave the way for copyright protection. This curation could be accepted as an exercise of skill and judgment. Sahni’s presence illustrates that an idea is expressed by exercising skill and judgment from his standpoint. However, under normal circumstances, we must not be able to register any tool together with a person. The designation of AI as the author necessarily requires us to conclude that RAGHAV also exercises skill and judgment and that its activity is not purely a mechanical exercise. I should note that the unpredictability provided by the AI system in creating the work has not prevented the registration of the work to the contrary to FWS Joint Sports Claimants v Canada[2].

How will moral rights be exercised in work in question?

Copyright Act s. 17.1 (1) provides two moral rights: The right to the integrity of the work and the right to be associated with the work. Although there is co-authorship, the natural person Sahni has complete control of these rights. However, considering the co-author, RAGHAV, the situation is not quite similar. If only an AI author were at issue, then would this registration mean completely ignoring the concept of moral rights? In this way, is this a waiver from the personal dimension of copyright law?

Under normal circumstances, each co-author reserves the right to be associated with the work and can enforce this right against each other, but if Sahni uses or exploits this work without specifying RAGHAV’s contribution, who will be able to oppose it? Maybe even if Sahni did not indicate that it is an AI-generated work in the first step and tried to register it, he would have been able to do it without anyone knowing about this AI contribution. In other words, co-authorship status does not create a difference in terms of moral rights, and the registration of an AI-generated work has not created the desired impact.

We can analyze the co-authorship logic and the equation between co-authors in more detail. In Seggie c. Roofdog Games Inc.[3], the court points to the line of case law that considers a common intention of parties to create a work of joint authorship to be relevant. How is this intention assessed in the presence of an AI indicated as a co-author? Someone’s intention to be a co-author with a brush or a monkey might be crucial in this regard?

How long is this work to be protected?

In the case of co-authorship, copyright shall subsist for the life of whichever of those authors dies last and for 50 years following the end of that year. However, such an assessment is not possible in terms of AI. For this reason, Sahni’s lifetime will be taken as a basis. As a result, the presence of AI did not make a difference at this point either.

There are numerous questions to ask, such as how does this registration differentiate from granting protection solely to Sahni? How are the defences to be implemented if this work infringes another copyrighted material? To conclude, if Sahni’s preferences are critical and practically no difference is made, why did two Offices prefer to register this work in such a way? Perhaps, to accept the existence of AI-generated works and provide more transparency to them in the copyright system.

As a final note, if you would like to contemplate more about AI-generated works, you can check out the Imitation Game exhibition at the Vancouver Art Gallery, which continues until October.

[1] “Aiva, l’incroyable IA qui compose des musiques”, online:Paper Jam <https://paperjam.lu/article/news-aiva-lincroyable-ia-qui-compose-des-musiques>.

[2] FWS Joint Sports Claimants v Canada (Copyright Board) (1991), 36 CPR (3d) 483 (FCA).

[3] Seggie c. Roofdog Games Inc., 2015 QCCS 6462 (CanLII), <https://canlii.ca/t/h2tkt>, retrieved on 2022-03-20

Copyright & Social Media

Copyright & Social Media Communications Law

Communications Law