Hi everyone!

I would like to share a recent Berlin Regional Court decision (Conway ./. Eder, 15 O 551/19) that I think is related to both our exam question and our discussions on the Andy Warhol Found. v. Goldsmith et al.[1]

This decision can be seen as a win regarding the appropriation art in the European Union (“EU”). It should be noted that, unlike Canadian copyright law, pastiche is an explicitly regulated exception in the European Union law. This concept was introduced with the InfoSoc Directive of 2001 as a copyright exemption with parody and caricature.[2] Then, while these exceptions were optional until 17 April 2019, they became mandatory for the Member States with the Directive on copyright and related rights in the Digital Single Market.[3] Thus, the Member States are obliged to implement this clause. For this reason, these exceptions have been recently transferred to the national laws of some Member States. Therefore, this decision is one of the first to apply the exception.

However, there is no reason why this exception should not be considered under the scope of the fair dealing exception in terms of Canadian copyright law. In fact, there is a third provision that brings the two concepts together. Section 30A(1) of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 reads as follows:[4]

“Fair dealing with a work for the purposes of caricature, parody or pastiche does not infringe copyright in the work.”

However, I would like to elaborate on this case to make the concept of pastiche more illustrative.

A “pastiche” defines an artistic work in a style that imitates that of another work, artist, or period. The term is derived from the French and Italian, which are based on the Latin word pasta, which means “paste.” [5]

Even though it is explicitly stipulated as an exception, there is no clear legal definition of pastiche in EU law.[6] Although there are rulings for caricature and parody exceptions regulated by the same provision, this is not available for the concept of pastiche. [7] For this reason, there are also debates about its definition. [8]

In some definitions, it is used interchangeably with the term collage, and sometimes, it approaches the term allusion. [9]Moreover, it has been debated whether sound sampling remains within this scope. [10]

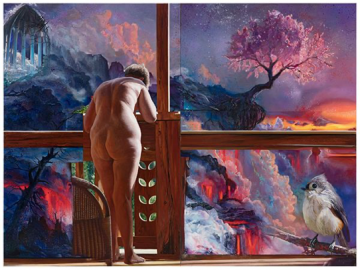

Martin Eder The Unknowable (2018/19). Oil on canvas. Photo: Uwe Walter, Berlin. Private Collection. Courtesy the artist VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2022

In the case at the bar, the painting above is an artistic work created by Martin Eder. Another artist, Daniel Conway, is the creator of the digital cherry tree image and claims that this painting copied his work.

The Berlin Regional Court decided that college-like integration of a digital work into a painting did not constitute an infringement and legally constituted a pastiche. [11] While relying on the pastiche exemption, the court also referred to the freedom of art[12], protected both by the German Constitution[13] and the EU Charter of Fundamental Rights[14].

As of 2022, the number of decisions in favor of appropriation art is increasing. Such decisions are very positive in the meme world and times of remixing culture. I think the following sentences of Eder, which are about the case, remind us of the connector model and are very illustrative of the Courts’ current approach towards these usages: “If I didn’t win, it could become more difficult for artists to quote other artworks […] We come from a culture of sampling.”[15]

References:

[1] Andy Warhol Found. v. Goldsmith et al., U.S., No. 21-869, cert. granted 3/28/22

[2] Directive 2001/29/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 22 May 2001 on the harmonisation of certain aspects of copyright and related rights in the information society, EP, CONSIL, 2001 Art. 5(3)(k).

[3] European Parliament European Council, “Directive (EU) 2019/ 790 of the European Parliament and of the Council – of 17 April 2019 – on copyright and related rights in the Digital Single Market and amending Directives 96/ 9/ EC and 2001/ 29/ EC” (2019) 34 Art. 17(7).

[4] “Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988”, online: <https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/1988/48/section/178/1996-12-01> Section 30A.

[5] Tan, David. “Parody, Satire, Caricature, and Pastiche: Fair Dealing Is No Laughing Matter” in Shyamkrishna Balganesh, Ng-Loy Wee Loon & Haochen Sun, eds, The Cambridge Handbook of Copyright Limitations and Exceptions, Cambridge Law Handbooks, ed (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2021) 324.

[6] Frédéric Döhl, “The concept of ‘pastiche’ in Directive 2001/29/EC in the light of the German case Metall auf Metall” (2017), online: <https://dspace.ub.uni-siegen.de/handle/ubsi/1820> at 49.

[7] Ibid.

[8] Mullin 2009: 105 f.; Bently/Sherman: 241–244; Lavik 2015: 83–85; Peukert 2014: 89; Mendis/Kretschmer 2013: 3; Haberstumpf 2015: 451; Stieper 2015: 304 f.; Ohly 2017: 968; cited in ibid.

[9] Ibid at 54.

[10] Ibid at 56.

[11] “Morrison & Foerster Successfully Helps Renowned Painter Martin Eder Win Landmark Copyright Case Before Berlin Regional Court – Copyright – Germany”, online: <https://www.mondaq.com/germany/copyright/1175100/morrison-foerster-successfully-helps-renowned-painter-martin-eder-win-landmark-copyright-case-before-berlin-regional-court>.

Newton Media, “New masters: painter’s win clarifies ‘pastiche’”, online: World IP Rev <https://www.worldipreview.com/article/new-masters-painter-s-win-clarifies-pastiche>.

[13] Deutscher Bundestag, “Basic Law for the Federal Republic of Germany” (1949) 140 Art. 5(3).

[14] European Parliament, “Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union”, (18 December 2000), online: <https://www.europarl.europa.eu/charter/pdf/text_en.pdf> Art. 13.

[15] Kate Brown, “How Meme Culture and a Landmark Legal Case Against an Artist in Germany May Loosen Europe’s Tight Copyright Regulations”, (11 April 2022), online: Artnet News <https://news.artnet.com/art-world/martin-eder-lawsuit-2091647>.

Copyright & Social Media

Copyright & Social Media Communications Law

Communications Law