My final project delves into the world of copyright infringement, or more specifically, whether an author’s fictional world, universe or setting can be subject to copyright infringement. It will also assess whether Large Language Models (LLMs) such as ChatGPT and Open AI can use literary works and distinctive features within these works, such as fictional worlds without infringing on an author’s copyright protections. To aid this investigation I will utilise George R.R Martin’s series of novels, adapted by HBO as the award-winning series Game of Thrones, to demonstrate my findings; with Martin filing a lawsuit against Open-AI for infringing on the copyright of his novels. Hopefully, you reach the end as I may have got slightly carried away in my writing!

vs

vs

Selling over 90 million copies since its inception in 1996, A Song of Ice and Fire is a tale of several noble households of Westeros (the fictional world where the series is set) fighting a multiparty war for the Iron Throne that features shifting alliances, conflicts, and betrayals. However, the storyline in Martin’s novels is not the only conflict of late, with the author suing Open AI’s decision to appropriate his work to train ChatGPT, their latest Large Language Model, without the author’s permission, triggering a series of copyright infringement allegations against the computer-generated software company.

The Ongoing Legal Battle

Martin’s copyright infringement claim accuses Open AI of inputting entireties of his literary works into Open AI’s software programs, in this case, ChatGPT, to train them to become more advanced.[i] These LLMs learn by analysing large amounts of data including books to develop the responses they generate when a user inputs information. This has resulted inMartin’s works being used by ChatGPT and generating to users of their own volition – without recognition of the author.

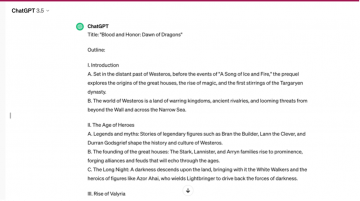

Martin states that ChatGPT is a “massive commercial enterprise that is reliant upon systematic theft on a mass scale,”[ii] after using his publications in the training of the technology. The infringement lawsuit cites specific ChatGPT prompts alleging that the program generated a mockingly similar outline for a prequel to A Song of Ice and Fire, titled A Dawn of Direwolves,[iii] appropriating the same characters from Martin’s existing books. Another example within the claim cites testimony from a fan, who used ChatGPT to create a version of the long-awaited sequel The Winds of Winter,[iv] based on content that ChatGPT had been trained on Martin’s existing works without express permission. Martin argues it is imperative that Open AI is found of infringing copyright protections and appeals for copyright legislation to prevent the delegitimization of creator credibility, stating that literary culture would be undermined without these protections. Without protections would cause a detrimental impact on the economies of not only the literary economy but also other creativity-centred mediums such as film, music and TV and would contradict the foundations of the copyright law of authors having the sole and moral rights to their works.

In response to the allegations of copyright infringement, Open AI has defended its use of the literary works outlining that their using of training data for the internet qualifies as fair use under US copyright law.[v] Open AI believes the company respects the rights of writers and authors, with the fair use doctrine under copyright law affording room for innovations like ChatGPT, which are at the forefront of artificial intelligence to serve to benefit users’ rights and wider society through the technology. This therefore begs the question of whether these works and the worlds that George R.R Martin created are protected under copyright, or whether the principle of fair dealing under Canadian copyright law allows this alleged infringement. The lawsuit also brings to the forefront of intellectual property law a broader concern in the media industry as to whether this type of technology is capable of displacing human-author content and whether the creators of computers and artificial intelligence models or even systems themselves can gain intellectual property rights for their outputs.

Subject to section 5(1) of the Copyrights Act R.S.C (1985), c. C-42[vi] copyright shall subsist in every ‘literary, dramatic musical and artistic work’ and under the rights of the copyright owner, in this case, Martin, can produce or reproduce the work and produce any translation, as well as the authorization of any of the named acts in Section 3(1)(a) – 3(1)(j).[vii] This legislation implies that without authorization, Open AI did not have the right to use his works to train the language model with his publications without permission.

Copyright in literary works protects not only the work itself but also any of its distinctive characters and storylines that are thorough and complete.[viii] Furthermore subject to s.27(1) of the Copyright Act R.S.C., 1985,[ix] it is an infringement of copyright for any person to do, without consent of the owner of the copyright, anything that by this Act only the owner of the copyright has the right to do to any substantial part in any material form. This legislation directly alludes to the foundations of Martin’s case against Open AI and forms the grounds for his case of copyright infringement.

In this case, stipulations that ChatGPT had unlawfully reproduced and generated versions of Martin’s texts using the same storylines and characters suggest that Open AI had created copies of Martin’s texts having inputted the whole of Martin’s texts into their system. These inputs as a result produced certain responses, including outlines and drafts of sequels with a mockingly similar plot, characters and fictional world. The combination of whole texts inputted, and substantial pieces of Martin’s writings outputted for the user’s answers may satisfy the requirement for infringement. This infringement was confirmed in Apple v Mackintosh[x], whereby the courts clarified the concept of novels to include “every volume, part or division of a volume.”[xi] This is vital in the determination of infringement as not only had Open AI utilized parts of Martin’s novel in its user output, but the entirety of the author’s works when training the system without authorised permission, which is highly indicative of an infringement of Martin’s copyright protections. Justice Reed went further in offering a liberal interpretation of this Act, stating the opening words had purposely been drafted broadly enough to encompass new technologies[xii] which had not been thought of when the act had been drafted making it applicable to the present dispute with the parameters of the statute encompassing technologies such as AI generated software.

Open AI defends that they cannot directly influence the output of the LLMs and that the purpose of their input of Martin’s text was to purely develop the LLM’s ability, the 1911 amendments of this act go further in stating that the legislation would not deny copyright protection to a work just because a copy could be characterised as part of the creation of a machine such as the hardware used to operate an LLM like ChatGPT. Although common law precedents such as Cinar v Robinson[xiii] have expressed the need for a balance between protecting authors’ rights and preventing statutory limitations on creative freedoms, the responses that the AI has extended beyond a requirement for creative liberties given the reproduction of whole drafts which damages the integrity of the author and the original literary work; moral rights the author is entitled to. Open AI allows responses to be generated using the characters and storylines Martin created which may serve to undermine the author’s reputation in violation of s.28(1).[xiv]

Amongst the research on Open AI’s use of Martin’s works, I decided to ask ChatGPT to write a draft of a sequel to Martin’s novels, creating characters, a storyline and a title.[xv] The results, unsurprisingly, support the author’s claim of creating a detailed outline of a book using the same character names, and storylines following on from Martin’s books, however a completely new name – that did bare some resemblance to the themes of the series of novels which can be depicted below, however, rather than A Dawn of Direwolves, my very own novel was called The Winds of Winterfell – not too far off from his sequel The Winds of Winter, although I have a feeling I’m on to a best seller.

Open AI has previously argued in similar cases that its models operate under the fair use doctrine, which promotes freedom of expression by permitting the unlicensed use of copyright-protected works in certain circumstances.[xvi] This argument was used in a similar case between US comedian Sarah Silverman and Open AI for copyright infringement of her material in training the firm’s AI system.[xvii] The California court upheld the unfair competition claim that OpenAI did not seek their permission to use their work for commercial profit.[xviii] I will try and establish how this may be viewed by the Canadian Courts as the US fair use has a much broader scope under US copyright laws, with fairness having the potential to be established even if the purpose of the use is not specified in the list, with a non-exhaustive nature allowing flexibility and adaptability depending on changes.[xix] I will also analyse the nuances of the difference between the two doctrines in the applicability of copyright infringement.

By comparison, under Canadian copyright law, the scope of the fair dealing doctrine by which copyright-protected works can be used without permission is much narrower. Subject to s.29 Copyright Act, fair dealing permits the use of a substantial part of another’s copyright protection expression without that person’s permission provided that the individual acts in furtherance of certain purposes in a fair manner with the eight exhaustive categories of purpose being research, private study, education, parody, satire, criticism, review, and news reporting.[xx] This doctrine helps Open AI defend its use of Martin’s works for the training of ChatGPT as it could be considered by a court for research purposes for the development of AI programming.

CCH v Law Society of Upper Canada sets out a two-stage test whereby the dealing’s use was for one of the listed purposes, and subsequently, the dealing must be fair.[xxi] This case positively articulated a modern interpretation of fair dealing encouraging a balance between protecting authors and promoting users’ rights in encouraging and disseminating creative and intellectual works and leaves a broader scope for the courts to interpret Open AI’s use as not infringing Martin’s rights. Therefore, subject to s.29 Copyright Act under the fair dealing doctrine Open AI could argue that using Martin’s literary works to train ChatGPT without his permission is for the purpose of research in the development of innovative technologies[xxii] which satisfies the first strand of the test. Open AI argued that users actively searching the author’s name and providing details of his works are actively recognising his works through which Martin will reap benefits, striking an appropriate balance between author and user rights.

The fair dealing category of research has a ‘large and liberal’[xxiii] interpretation to ensure users’ rights are not constrained. However, ultimately, I believe that the courts would find in favour of Martin because the dealing was not fair under the second strand of the test outlined in CCH v LSUC. Open AI’s use of the whole text, whilst not definitively unfair, is on the higher end of the scale determining the amount of the dealing. The case exemplifies that the use of Martin’s literary work has not been utilized in LLM training, but to the extent where characters, storylines, and fictional worlds are reproduced and made available for ChatGPT users to plagiarize. This means that these copies can reach wider public dissemination, of which the nature of these new works can no longer be assured as unpublished works, which has the potential to undermine the dignity of Martin’s works and credibility as an author; a concern of which Martin stresses in the lawsuit. This potential failure to satisfy the second strand of the test in CCH would likely mean that Open AI would be infringing the copyright of Martin’s works under a Canadian stance. Whilst no outcome has been reached and this is not definitive of how the court would find the outcome in this case under Canadian jurisdiction, it is an attempt to explore the different aspects of the Copyright Act.

In the recent climate, there has been much opposition to Open AI’s use of literary works to train LLMs such as ChatGPT with critics highlighting that the court’s permittance of this use will incite a broader battle to defend authors from unauthorised exploitation by generative AI technology for copyright infringement to ensure literary works are not used without author’s permissions.[xxiv] With similar suits against other authors against Open AI, as well as other tech giants, such as META, it is clear the intersection between artificial intelligence and copyright law is headed for unprecedented scrutiny in courts. The lawsuit’s conclusion will help establish and clarify the boundaries of the fair use doctrine and copyright protections of IP in the training of AI language models in the US, presupposing such a conclusion in the Canadian legal system whilst looking at the distinctions between Canadian ‘fair dealing and American ‘fair use’ doctrines.

Should worlds be copyrightable?

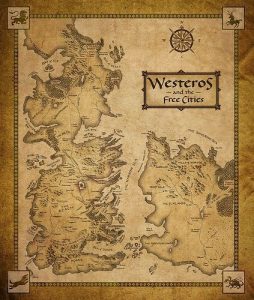

It is well established in Canadian copyright law that characters and storylines are protected under the Copyright Act. However, the setting or world in which the story is set has not been explicitly commented on by Canadian courts, presenting a statutory gap and vulnerability for copyright infringement. The Canadian legal system would benefit from addressing this statutory gap by clarifying the extent of copyright protections pertaining to an author’s created ‘world’ such as the Marvel Universe, Tolkien’s “Middle Earth” and Martin’s Seven Kingdoms, with Westeros and Esos featuring most in his novels. Similar unique features of George R.R Martin’s novels such as the fictional languages of Dothraki and High Valyrian have been deemed not protected under copyright law following the Paramount v Axonar[xxv] case, as languages are intricate frameworks of vocabulary, syntax, grammar, and phonetics, which by themselves do not convey the meaning, which is classified as systems, which are not subject to copyright protection.[xxvi] This examination by the courts may be an indicative feature of how Canadian courts may address fictional worlds with the names of places simply systems that cannot be protected.[xxvii]

However, a composite fictional world formed of original expressions presents a different problem with unique concepts such as ‘Westeros’ distinct characteristics which are used to build upon characters and storylines using the world as a backdrop for the novels the line is harder to draw because it conveys a meaning which may be more likely to be protected under the Copyright Act. Upon closer inspection, arguably, most fictional universes are derivative from other works themselves which may mean they are less likely to be protected from copyright if the worlds themselves are sources of other works. The film Avatar can be traced to a variety of sources from Pocahontas [xxviii] Even in Martins’ first novel “A Song of Fire and Ice” the dragons, white walkers, and city names are drawn from other sources[xxix], which may mean it cannot be protected in its own right. Given that much creative expression is in itself derivative, LLM responses derived from other artworks can be likened to the human creative process: by taking influence from other works. Open AI’s use of Martin’s work may be in accordance with Canadian copyright law’s promotion of users’ rights to shape the creative world in much the same way authors and artists have previously.

To promote freedom of artistic expression across mediums such as through fanfiction the ruling would benefit to acknowledge the role of new technologies in the applicability of fair dealing. Much like storylines and characters to protect the interests of authors from generative AI, such as ChatGPT, worlds should be protected under copyright legislation, however allowing use under the doctrine of fair dealing to promote public interest and further inclusion and empowerment of society and culture.

Bibliography

[i] Gerken, Tom “Game of Thrones author sues ChatGPT owner OpenAI” (21st September 2023), online: BBC News < https://www.bbc.com/news/technology-66866577>

[ii] Gerken, Tom “Game of Thrones author sues ChatGPT owner OpenAI” (21st September 2023), online: BBC News < https://www.bbc.com/news/technology-66866577>

[iii] Ibid

[iv] Ibid

[v] Khatar, Perla “George R.R Martin Won’t Bend The Knee” (2023) Journal of Law and Technology, University Richmond School of Law, online: < https://jolt.richmond.edu/2023/10/20/george-r-r-martin-wont-bend-the-knee-chat-gpt-generative-ai-and-the-fine-line-between-fair-use-and-copyright-infringement/>

[vi] Copyright Act R.S.C., 1985 c.C-42, s.5(1)

[vii] Copyright Act R.S.C., 1985 c.C-42, s. 3(1)(a) – 3(1)(j).

[viii] Jamar, Steven. “When the author owns the world: Copyright issues arising from monetizing fan fiction”, (May 2014), online: Institute for Intellectual Property <https://www.researchgate.net/publication/265167047_When_the_Author_Owns_the_World_Copyright_Issues_Arising_from_Monetizing_Fan_Fiction>.

[ix] Copyright Act R.S.C., 1985 c.C-42, s.27.1

[x] Apple Computer Incorporated v Mackintosh Computers LTD (1990) SCC 209.

[xi] Ibid

[xii] Ibid

[xiii][xiii] Cinar v Robinson (2013) SCC 73

[xiv] Copyright Act R.S.C., 1985 c.C-42, s.28.1

[xvi] Brittain, Blake “OpenAI gets partial win in authors’ US copyright lawsuit”, (13th February 2024), online: Reuters < https://www.reuters.com/legal/litigation/openai-gets-partial-win-authors-us-copyright-lawsuit-2024-02-13/>

[xvii] Vallance, Chris. “Sarah Silverman Sues OpenAI and Meta”, (12th July 2023), online: BBC News <https://www.bbc.com/news/technology-66164228>

[xviii] Wilson, Cho “Authors See Most Claims against OpenAI dismissed by judge” (13th February 2024), online: The Hollywood Reporter <https://www.hollywoodreporter.com/business/business-news/sarah-silverman-openai-lawsuit-claims-judge-1235823924/>

[xix] Kulkarni, Achyut “Comparison Between Fair Use and Fair Dealing” (17th Sept 2022) online: IP Matters <https://www.theipmatters.com/post/comparison-between-fair-use-and-fair-dealing#:~:text=Fair%20dealing%20has%20a%20narrower,to%20changes%20leading%20to%20uncertainty>

[xx] Copyright Act R.S.C., 1985 c.C-42, s.29

[xxi] CCH Canadian Ltd v Law Society of Upper Canada (2004) SCC 13

[xxii] Copyright Act R.S.C., 1985 c.C-42, s.29

[xxiii] CCH Canadian Ltd v Law Society of Upper Canada (2004) SCC 13

[xxiv] Shanbhag, Maya “Letter from Authors Guild President Maya Shanbhag Lang About Class-Action Suit Against OpenAI” (20th September 2023) Online: The Authors Guild < https://authorsguild.org/news/letter-from-ag-president-maya-lang-about-openai-suit/>

[xxv] Paramount Pictures Corporation v Axanar Productions (2017), USDC, C.D Calafornia.

[xxvi] Khatar, Perla “George R.R Martin Won’t Bend The Knee” (2023) Journal of Law and Technology, University Richmond School of Law, online: < https://jolt.richmond.edu/2023/10/20/george-r-r-martin-wont-bend-the-knee-chat-gpt-generative-ai-and-the-fine-line-between-fair-use-and-copyright-infringement/>

[xxviii] Jamar, Steven. “When the author owns the world: Copyright issues arising from monetizing fan fiction”, (May 2014), online: Institute for Intellectual Property <https://www.researchgate.net/publication/265167047_When_the_Author_Owns_the_World_Copyright_Issues_Arising_from_Monetizing_Fan_Fiction>

[xxix] “George R.R Martin on how he comes up with his character names” (2015) on Youtube: < https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nTBQZBMQtOw&t=46s>

Copyright & Social Media

Copyright & Social Media Communications Law

Communications Law