Hi everyone! There have been some questions about samples, so I decided to write this piece that touches upon use and history of sampling, and also considers why copyright owners don’t sue more frequently over the use of samples.

Defining “samples”

Samples are short pieces of recorded music or sounds that can be inserted into other pieces of music or may by themselves be arranged to make a track. Artists sometimes sample other musical works, but samples of single notes or hits of an instrument, the artist’s own music productions, or audio from movies, TV, the news and more are also common. The appeal of sampling comes not just from the ability to replay a “catchy” piece of sound, but also the potential to manipulate, replay, or otherwise creatively alter samples. Tracks that are composed purely of samples are common in many genres, including hip-hop, drum’n’bass, techno, and many other types of electronic music.

A brief history of sampling

Sampling has its origins with sound artists from the 1940s who made “music concrete”, a style of music that involved layering of sounds on audio tape. Many of the sounds that were layered were “found sounds” from the environment that they recorded onto the tape, and occasionally included pieces of other music.

Sampling further developed in the 1950s and 60s with the development of a keyboard instrument called the Mellotron. When the keys of the Mellotron were played, tape loops were triggered, playing pre-recorded sounds, i.e. samples. The Mellotron was used by the Beatles in the opening of Bungalow Bill and also for the flute sound in “Strawberry Fields Forever”.

But sampling really took off in the 1970s when it began to be used by hip-hop artists. The early hip-hop artists used a form of live sampling during performances where a DJ would play bits of records, with an MC providing vocals. Eventually, some of these performances were recorded to vinyl, fixating the sounds and providing the first instances of infringement in the context of hip-hop.

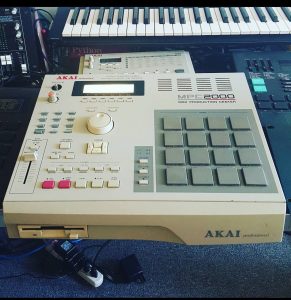

In the 1980s, commercially available synthesizers became much more affordable (and portable!), which escalated use of sampling. Samplers of the 1980s by companies like Akai and Korg also started to include “sequencing” capability which allowed artists to arrange samples to easily form whole tracks. Sampling became an essential part of hip-hop and also the basis for other genres of electronic music, ranging from techno to house to drum’n’bass.

My Akai MPC 2000, originally released in 1997. The first Akai sampler was from 1988, and they continue to make some of the best hardware samplers today. The early samplers had short internal memory stores or used floppy discs which limited the length and number of samples that could be used. Most people sample using software these days, which is much less cumbersome!

The 1980s was also the period when the first famous lawsuits over copyright infringement from use of samples first appeared. Some of these have been touched upon by others so I won’t go into them here. But it’s clear that the music industry was having difficulty grappling with this new technology, and those struggles continue today, though litigation seems to have become less common.

Why don’t people enforce copyright on their samples?

A first reason why people don’t enforce is related to access to justice issues. Many people, even people who have released records, simply do not have resources to mount lawsuits. This was sadly the case with the “Amen Break”, which is perhaps the most frequently used sample, appearing in over 6000 tracks including ones by successful artists like Oasis, Tyler the Creator, Skrillex, NWA, the Prodigy, and Jay-Z, and forming the basis of the jungle/drum’n’bass genres. The Amen Break came the song “Amen Brother” which was released by The Winstons in 1969. The Winstons never saw any royalties or payment from the sample, in part because they did not have resources to sue. In 2015, British DJs who were fans of the use of the sample made a GoFundMe that delivered £25000 to the frontman of the Winstons. Sadly, the drummer who played the break, Gregory Coleman, died before this happened and was homeless at the time.

Chopped Amen Break, played at different speeds: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qwQLk7NcpO4

“Amen Brother” by the Winstons: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GxZuq57_bYM

The Amen Break story also points to another reason why copyright on samples is sometimes not enforced: limitation periods. The Winstons never found out about the use of their samples until several years after they had started to be used frequently in jungle and drum’n’bass music. The statute of limitations for copyright infringement suits in the US is 3 years after the work is infringed, so the Winstons would not have been able to enforce the copyright in many instances of infringement.

For artists with more resources, licencing or “clearance” of the samples is one option to avoid litigation. Some artists purchase sample libraries, which are collections of samples that have already been licenced from the copyright owners. Of course, obtaining licences for individual samples requires time, funds, and negotiation skills, and many artists opt for a “use first, worry later” strategy. Given the volume of music that is sampled and produced by sampling, it can be difficult even for major labels owning the rights to well-known works to enforce copyright. Enforcement typically happens when the track reaches sufficient popularity that the producer who sampled becomes visible and is making money off the track, which is what enables the “use first, worry later” strategy to work in the vast majority of cases.

But our discussions in class point to perhaps the largest reason why people don’t sue over samples: sampling is part of electronic music creation and culture. As noted above, sampling is a key pillar of modern electronic music production, in many cases forming the basis for whole tracks. If sampling is accepted as a necessary part of the creative process, this would discourage enforcement from the artist’s perspective.

On the other hand, the Amen Break story perhaps suggests that the balance between creator’s and user’s rights in sampling is weighed unjustly against the original creators. Copyright law is not providing adequate compensation to creators when their works have been infringed, nor is it promoting creative use of samples. Perhaps the scale of sampling in modern music make these tasks impossible from a legal perspective. If this is the case, then initiatives within the community and efforts by artists themselves to ensure they have adequately attributed and compensated (where possible) other artists may provide the means for works to be used fairly where the law has not.

Some articles & pages I consulted while writing this:

https://www.producertech.com/blog/a-brief-history-of-sampling-in-music

https://create.routenote.com/blog/origin-history-of-sampling/

https://www.thomann.de/blog/en/a-brief-history-of-sampling/

https://www.whosampled.com/The-Winstons/Amen,-Brother/sampled/

https://www.bbc.com/news/entertainment-arts-34785551

Copyright & Social Media

Copyright & Social Media Communications Law

Communications Law