This paper will demonstrate how the current status quo on copyright and trademark in fashion law is detrimental to modern online small fashion brands which are wrongly seen as utilitarian rather than artistic. This applies to those which gain popularity from social media, or whose presence is mainly online or otherwise created by modern technology.

It is first important to show how the utilitarian perspective is hegemonic in fashion law, originating from outdated sexist beliefs in copyright law. The grounding principles in copyright are fixed original expressions. As per the Canadian Copyright Act, copyright is a protection given to original artistic works. Facts or things grounded in fact are not given copyright protection under the doctrine of functionality found affirmed in Kirbi AG v Ritvik Holdings Inc. 2005. Rooted in sexism, copyright has interpreted stereotypically female-industries such as cooking recipes or fashion to be factual and not artistic, and thus are not offered copyright protection. This has occurred in fashion although we can never totally remove creativity from fashion designs. This has never been widely challenged as it is non-harmful and possibly even beneficial to larger brands who can copy any element of any garment but it is ill fitting for the growth of fashion brands today.

Today, small up-and-coming brands have the opportunity for their unique designs to go viral on social media. Logic would suggest this as a method to grow one’s brand, but large brands get away with stealing designs from smaller companies because fashion is not fully protected. The current system makes it an easy way for larger brands to copy the viral design leaving the newcomer in the dust.

The utilitarian perspective is unsuitable to new social media brands and modern designs.

Those recent fashion trends have seen online designers explode in popularity. Using photoshop and design technology, brands can create clothing designs without even picking up a sewing kit. This is more than just cut and paste; brands work with videos and images of models and celebrities and have wholly virtual ad campaigns that influence day-to-day trends (see images 1-2). New fashion brands are utilising these virtual designs to gain and gauge popularity prior to creating wearable pieces, or the designs remain virtual. This places modern fashion squarely within the field of art and not fact or utility. Combined with the fact that larger brands can easily copy them without fear of infringement, this is wholly unjust and antithetical to the original purpose of copyright; to protect fixed forms of art.

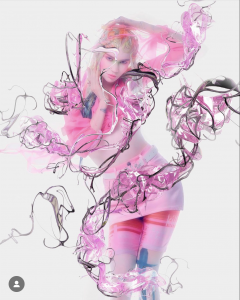

Further cementing fashion into the art-world, small modern designers are utilising newly accessible technology to create clothing that can be seen in no other lens than an artistic one; designer-artists are creating wearable sculptures (see images 3-4). These are not ‘useful’ pieces of textile clothing; they are fashion today, they are creative, and they deserve the same protection allowed to all other forms of art, to prevent the unjust copying of their work.

There are possible answers in trademark protection and artwork separability. Trademark has traditionally meant to be a sign or combination of signs that is used or proposed to be used by a person for the purpose of distinguishing or so as to distinguish their goods or services from those of others, as per The Trademarks Act (TMA). New York has expanded trademark protection to cover more than just a brand logo. In a landmark case Christian Louboutin LLC v Yves Saint Laurent America Inc, 2013. Louboutin gained trademark over their signature shade of red in all of their heel designs as it acquired a secondary meaning as a distinctive symbol that identifies the Louboutin brand. Secondary meaning means those descriptive words or aspects which indicate the source of the product or service. It is established as a doctrine to prevent any person putting off their goods as those made by a rival. Secondary meaning has long standing ground in Canadian jurisprudence. Most notably, the expansion of the trademark has occurred in the case of Glaxo Wellcome Inc. v. Novopharm Ltd. 2000 where it was stated that the shape of a pill could constitute an albeit weak mark. As well, the TMA expanded what could constitute a sign (distinguishing mark). may now be a Although it would be difficult for a smaller brand to establish the importance of a trademark decoration to a piece, as well as its reputation in the public eye, this opens the door for small brands to trademark decorative aspects of their viral (and likely recognizable) designs as those with such secondary meaning, expanding secondary meaning can be a solution to protecting these small Canadian brands..

In the landmark case Star Athletica LLC v Varsity Brands, Inc 2016 The US Supreme Court has created a separability test for fashion; separating the artistic creativity of the designs placed onto clothing and offering copyright if the design on a useful article can be perceived as artwork on its own. The test was established for a feature incorporated into the design of a useful article is eligible for copyright protection only if the feature (1) can be perceived as a two- or three-dimensional work of art separate from the useful article, and (2) would qualify as a protectable pictorial, graphic, or sculptural work—either on its own or fixed in some other tangible medium of expression—if it were imagined separately from the useful article into which it is incorporated. This could be beneficial to those designers of wearable art and readily incorporated into Canadian copyright law.

Copyright laws and interpretations need to be expanded to protect modern online small fashion brands today. Many are prima facie works of art and are not purely useful articles of clothing; most notably wearable artwork that readily fits into a test of separability, and brands with viral recognizable trends on social media which can find a solution in the use of secondary meaning in expanded trademark law. Through this, small online brands can protect themselves from the current state of affairs where they are being exploited by larger brands. Big brands can have their cake and eat it; modern designers are screaming for a revolution.

Images 1 and 2; Virtual clothing campaigns

Virtual clothing campaign

Virtual clothing campaign

Images 3 and 4; Wearable sculptures

Wearable sculpture

Wearable sculpture

Works Cited

Anna Bartow, “Fair Use and the Fairer Sex: Gender, Feminism, and Copyright Law” in Journal of Gender, Social Policy & the Law 3 (American University: 2006)14

Chavie Lieber, “Fashion Brands Steal Design Ideas All The Time And It’s Completely Legal”(27 April 2018), online: Vox <https://www.vox.com/2018/4/27/17281022/fashion-brands-knockoffs-copyright-stolen-designs-old-navy-zara-h-and-m>

Christian Louboutin S.A. v. Yves Saint Laurent America Holding, Inc. 696 F (3d) 206 (2012), modification denied, 709 F (3d) 140 (2013)

Copyright Act, RSC, 1985, c C-42

Delrina Corp v Triolet Systems Inc 2002

Frank Reddaway and Frank Reddaway & Co Limited v George Banham & Co, Limited 1896 AC 199

Glaxo Wellcome Inc. v. Novopharm Ltd. 2000, 195 FTR 98

Greg Hagen et al, Canadian Intellectual Property Law, 3rd ed (Toronto: Emond Montgomery, 2022)

Kirkbi AG v. Ritvik Holdings Inc., 2005 SCC 65

Moreau v St Vincent 1950 EX CR 198 at para 203

Novopharm Ltd v Bayer Inc, 2000 2 FC 55

Orushw23ft, Checkthetag, (6 November 2022), online: instagram

Outside.inc (19 April 2022), online: instagram

Ray Plastics Ltd. v. Dustbane Products 1994 OAC 74

Star Athletica, LLC v. Varsity Brands, Inc. 15 US 866 (2017)

Ted Talk, “Joanna Blakely – Lessons From Fashion’s Free Culture” (29 January 2005) at 02m:54s, online (https://www.ted.com/talks/johanna_blakley_lessons_from_fashion_s_free_culture?language=en)

Trademarks Act, RSC, 1985, c T-13

Yinqingyin, Spotlighttime, (5 November 2022), online: instagram

888vampires (20 September 2022), online: instagram

Copyright & Social Media

Copyright & Social Media Communications Law

Communications Law

Since the beginning of the course I have fascinated by how certain industries like art or fashion or recipes have had less protection by copyright and trademark. I see that changing with both the recognition that large brands are copying smaller brands in both design and artwork (notably the recent Banksy case). I think that is an important as Joanna Blakely’s ted talk missed this issue that has progressed in modern copyright law. With the 2014 amendments in the trademark act section 2 I strongly see this issue being brought to court in the future. In Glaxo v Novopharm 2000, we see the door being opened to trademark that is more protective of creative industries. In combination with the Trademarks Sci amendments and recognition of the issue, I see this trend progressing in Canadian jurisprudence.