*Please note that I wrote this to post before class 2, so it only covers the course material from class 1 and week 2 readings:

Hey everyone, the Kenrick & Co v Lawrence & Co case from our first class about a drawing of a hand reminded me of one of the most memorable copyright disputes in sports: Leonard v Nike Inc.

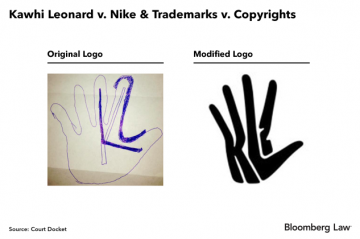

The background for the dispute was Kawhi Leonard—widely known for leading the Toronto Raptors to their 2019 NBA championship and being a “fun guy”—had an endorsement deal with Nike during the 2010s. Nike created and used a logo incorporating Kawhi’s initials and jersey number that is shaped like a hand on all of its Kawhi Leonard merchandise during this period. Of course, Nike also registered the logo with the US Copyright Office. In 2018, Kawhi left Nike for New Balance and wanted to take his logo with him. So, he applied for a court declaration that he is the sole author of the logo and that Nike engaged in fraud by registering the logo without his consent. Kawhi based his claim on the fact that he provided a “rough copy” of the logo, based on which Nike created the final logo.

Interestingly, one of the arguments Nike advanced in response was that its endorsement deal with Kawhi meant that he was in part under Nike’s employment when he provided the rough copy of the logo, rendering his contribution a “work made for hire.” While this case took place in the US, this doctrine that Nike relied on seems to coincide closely with the Copyright Act’s s. 13(3) employment exception from this week’s readings.

Ultimately, the District Judge sided with Nike: “‘It’s not merely a derivative work of the sketch itself,’ he said in his ruling, per Maxine Bernstein of The Oregonian. ‘I do find it to be new and significantly different from the design.’”

If this case took place in Canada, I think that our courts would have come to the same conclusion. Nike unquestionably took Kawhi’s idea of a hand-shaped logo incorporating his initial and jersey number, but, in my opinion, its expression of said idea was significantly different than Kawhi’s rough copy. Nike’s logo is also clearly original, as required by s. 5(1): It is not a “purely mechanical exercise,” since Nike did not just copy Kawhi’s design, but produced a significantly distinct design that clearly required a great degree of skill and judgment (CCH v Law Society).

With that said, I’ll let you decide for yourself who you side with in this dispute:

According to his attorney, “Kawhi put his heart and soul into that design.” I’m just glad for Kawhi’s sake that he decided to pursue basketball, rather than fine arts.

Copyright & Social Media

Copyright & Social Media Communications Law

Communications Law