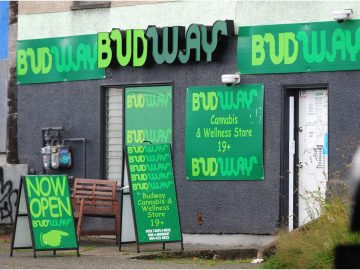

This summer, I was driving down Clark drive when I saw what I believed to be the Subway logo on a store front; however, upon closer inspection, I realized the logo said “Budway”. I googled “Budway” and discovered it was a cannabis store. I wondered how Budway could be getting away with such a blatant copy of Subway’s branding…

Once we learned about passing off and trademark infringement in IP Law, I asked myself a more specific question: could Subway win an action against Budway for passing off and/or trademark infringement? Upon researching the issue, I discovered that Subway had already sued Budway! In June of 2021, the Federal Court (“FC”) released its decision in Subway IP LLC v Budway, Cannabis & Wellness Store, 2021 FC 583 (“Subway v Budway”). Subway IP LLC, which owns Canadian registered trademarks used in association with SUBWAY-branded sandwich restaurants, brought an application to the FC to enjoin the respondents from using the BUDWAY trademark in association with a “Cannabis & Wellness Store”. The FC found that the BUDWAY trademark infringes the registered trademarks of Subway and amounts to both passing off and depreciation of the goodwill in those marks, contrary to sections 7(b), 20, and 22 of the Trademarks Act, RSC 1985, c T-13. The FC issued an injunction, awarded damages in the amount of $15,000 and costs in the amount of $25,000.

The FC held that Subway had goodwill in Canada, and this goodwill was reinforced by Budway taking advantage of that goodwill by copying Subway’s logo and using a mascot in the form of a submarine sandwich filled with cannabis leaves and bloodshot eyes. The misrepresentation alleged by Subway was the likely confusion of Budway with its trademarks. Subway did not contend that they suffered financial harm. Rather, they relied on the loss of control over the use and commercial impact of their marks. The FC agreed, stating that Subway’s loss of control over their marks and the resulting harm to their goodwill arising from the respondents’ conduct was sufficient to meet the third element of the passing off test.

The FC’s analysis of passing off in Subway v Budway led me to consider the meaning of deception in passing off claims and the purpose of passing off actions. The FC seemed to rely on a watered-down definition of deception, which was at odds with the concept of deception in Institut national des appellations d’origine des vins et eaux-de-vie et al v Andres Wines Ltd. et al (1987), 60 OR (2d) (“Institut national”). In Institut national, the Ontario court held that Canadian sparkling wine marketing itself as “champagne” did not deceive consumers into thinking they were buying champagne, because Canadian champagne is a distinct product not likely to be confused or compared with French Champagne. It seems absurd that consumers are not expected to be deceived into thinking that a sparkling wine product labelled champagne is champagne, and yet are expected to be deceived into thinking cannabis products are associated with a sandwich shop.

While I understand that the “test person” used to assess confusion in the passing off analysis varies depending on product type, the FC’s approach to the confusion analysis in Subway v Budway overlooks the original purpose of passing off claims: protecting a trader against a competitor who creates a likelihood of confusion in the marketplace as to the source of their goods and services (Greg Hagen et al., Canadian Intellectual Property Law: Cases and Materials, 2nd ed. (Toronto: Emond Montgomery, 2018) at 318). Consumer deception seems more likely to occur as a result of Canadian sparkling wine producers labelling their product as “champagne” than as a result of a cannabis shop parodying the logo of a sandwich franchise. In my view, the purpose of passing off would have been served by holding sparkling wine producers liable in Institut national but it is not equally served by holding Budway liable in Subway v Budway. Not only are Subway and Budway not in competition with one another in the marketplace, but also Budway is a parody of Subway rather than an attempt to confuse consumers as to the source of Budway’s goods. Holding Budway liable for passing off necessitates diluting the “confusion” element of the tripartite passing off test and centering the bulk of the analysis on whether Budway capitalized on Subway’s goodwill.

To avoid departing from the core purpose of passing off, which is the protection of a trader against a competitor who created a likelihood of confusion in the marketplace by causing confusion as to the source of their goods or services, the FC should have developed a cause of action to address parody brands who take advantage of an established brand’s goodwill. Specifically, the FC should have used Subway v Budway as an opportunity to develop the doctrine of initial interest confusion in Canada. Initial interest confusion refers to the use of another’s trademark in a manner calculated to capture initial consumer attention, even though no actual sale is completed as a result of the confusion. “Confusion” in the context of initial interest confusion has a lower threshold than in passing off. For initial interest confusion, it is confusion as to association, endorsement, or approval; the test considers whether the defendant’s use of the plaintiff’s mark evoked “initial interest” in a potential consumer even if it did not result in a sale. This is the type of confusion in Subway v Budway: even if consumers were initially confused by Budway’s mark, this confusion would be dispelled by the time that the purchaser saw cannabis products for sale rather than sandwiches.

In class, we discussed how the hesitancy to adopt initial interest confusion in Canada stems from its potential to serve as a weapon for keeping legitimate competitors out of the market. Subway v Budway would have been an ideal case to develop this doctrine because the concern for keeping legitimate competitors out of the market doesn’t apply: Budway and Subway are not competitors. Developing initial interest confusion to deal with parody brands will allow companies to access a remedy when their goodwill is being taken advantage of without diluting the traditional law of passing off, which is designed to protect against unfair competition.

Do you agree with the Federal Court’s analysis of deception in Subway v Budway? Do you think analyzing Subway’s claim through the framework of initial interest confusion would have been more appropriate?

Copyright & Social Media

Copyright & Social Media Communications Law

Communications Law