Term Paper by Jessica Goodridge

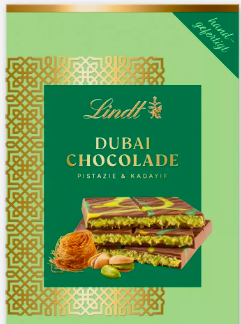

If you are a food lover like me, or are active on any form of social media, I am sure you have heard of the viral confection called “Dubai chocolate.” Dubai chocolate refers to a milk chocolate bar containing pistachio filling and kadayif, a Middle Eastern crispy phyllo dough. It was created in Dubai, United Arab Emirates by Sarah Hamouda, a social media influencer and owner of Fix Dessert Chocolatier (“Fix”). She named the original bar “Can’t Get Knafeh of It”, making reference to another name for the crispy phyllo found inside the bar. Since the bar’s creation it has blown up in popularity, gaining worldwide fame for its unique flavour profile and presentation. It has inspired all sorts of spin-off treats such as Dubai chocolate waffles, crepes, and lattes.[1] Even long-established brands like Lindt Chocolatier have made their own version of Dubai chocolate, hopping on the burgeoning trend. As Dubai chocolate continues to grow in popularity, what intellectual property considerations do Canadian trend-hoppers have to consider if they make their own Dubai chocolate or food inspired by it?

Is the recipe for Dubai chocolate copyrightable?

Under Canadian copyright law, the recipe for Dubai chocolate would not be copyrightable because recipes are seen as akin to facts or formulas, which are not protected by copyright.[2] If a recipe contains a significant literary explanation, it may be copyrightable because Canadian copyright law does protect “substantial literary expressions, which can include descriptions, illustrations, anecdotes, commentaries, or compilations.”[3] However, it is unlikely that the recipe for the composition of the chocolate bar itself, consisting of chocolate, pistachio filling, and kadayif, would receive copyright protection in Canada.

Would Fix succeed in a passing off claim in Canada?

As we have learned in this course, passing off is a common law tort and statutory cause of action under the Canadian Trademarks Act that allows companies to make a claim against competitors they believe are deceiving consumers in the marketplace.[4] The elements of passing off are the existence of goodwill, deception of the public due to a misrepresentation, and actual or potential damages to the plaintiff.[5]

First, Fix would need to establish that despite being a company based in Dubai, they have established goodwill in Canada.[6] The biggest hurdle to establishing goodwill in Canada is that Fix’s original Dubai chocolate bar is currently only sold in Dubai and Abu Dhabi, so the actual product is not on grocery store shelves anywhere in Canada. However, goodwill can exist outside of the area where a company carries on business and can be based on the good’s reputation in the particular area.[7] With around 386,000 followers on TikTok and 590,000 followers on Instagram, it is fair to say that Fix has a significant internet presence that could translate to foreign goodwill in Canada.

Next, to succeed in a passing off claim, Fix would need to establish that other companies calling their chocolate “Dubai chocolate” deceives the public due to misrepresentation as to the chocolate’s source. Fix could argue that competitors using the term “Dubai chocolate” indicates to consumers that the chocolate and other ingredients come from Dubai and are the chocolate bars created by Fix themselves. The test person in Canada of the “shopper in a hurry”[8] picking up a relatively inexpensive chocolate bar might believe that the Dubai chocolate they are buying is made by the original source, Fix, despite it being made by a competing company.

A German court was recently posed a question about whether Dubai chocolate causes consumer confusion in the context of passing off and trademark law.[9] A court in Cologne held that Dubai chocolate can only be labelled as such if it comes from the United Arab Emirates, otherwise it leads to customer confusion as customers assume that the product is made in Dubai and imported to Germany. The product in question in the German lawsuit, made by supermarket chain Aldi, was called “Aldyan Dubai Handmade Chocolate,” but since it was actually made in Turkey, courts were concerned about consumer deception. This case was brought by the official German importer of Fix against the supermarkets Aldi and Lidl and the chocolatier Lindt. The defendants argued that the term “Dubai chocolate” was generic, only referring to the general type of chocolate with pistachio and kadayif filling, not specifically to chocolate that hails from the Dubai region.

This is quite similar to the arguments made in Institut National v Andres Wines.[10] There the defendant argued that he could use the term “champagne” for his Ontario product as it had become a generic term for a sparkling wine. However, the plaintiffs argued that the term “champagne” carried goodwill as it indicated a specific grape, area of growth, and method of production that should be protected from incursion by wines that do not meet the stringent regulation requirements. The court found that champagne had become “semi-generic”, not entirely diluted to the extent that it only refers to a class of products, and could still refer to particular merchants and their products. It appears that the German court finds similarly that Dubai chocolate is not yet fully generic because it holds meaning as a geographic indicator and also points to a particular merchant and their product.

Note the change in Lindt’s branding from “Dubai Chocolate” to “Dubai-Style Chocolate”!

Finally, to establish passing off in Canada, Fix would need to prove damage through either loss of goodwill and reputation[11] or loss of trade.[12] Fix could argue that when competitors pass off inferior products as Dubai chocolate, dissatisfied customers who think they have purchased from Fix may decide not to purchase from them in the future and tell people they know not to purchase Dubai chocolate, which could lead to a reduction in their reputation worldwide. Fix may struggle to establish loss of trade because their chocolate bars are not actually available for purchase in Canada, so a consumer buying a competitor’s product does not necessarily cut into Fix’s profits. As it stands, Fix is actively taking steps to warn consumers about resellers, particularly resellers located in Dubai, stating on their Instagram that bars not actually purchased directly from Fix are likely not authentic. This shows clear concern on their part about competitors passing off their “Dubai chocolate” as the original chocolate bar created by Fix. The tort of passing off could be one way for Fix to protect consumers from deceptive businesses riding the coattails of their trending chocolate.

Can the term “Dubai chocolate” be trademarked in Canada?

A final way that Fix could protect the authenticity of their chocolate is to register a trademark for the term “Dubai chocolate” in Canada. There are currently two applications for trademarks with the Canadian Trademark Office that include the term “Dubai chocolate:” one for “Flair Dubai Chocolate” and one for “Lindt Dubai Chocolate.”[13] Neither of these trademarks were applied for by Fix, both are competitors applying for the trademark and both applications are from 2025. Neither has been confirmed as a trademark by the Registrar. However, I think that both of these marks and any potential trademark applied for by Fix would have hard time meeting Canadian registration requirements. The term “Dubai chocolate” would likely either be unregistrable due to being clearly descriptive of the character of the wares contrary to section 12(1)(b) of the Trademarks Act, or the name in any language of the wares in connection with which it used contrary to section 12(1)(c).[14] The term “Dubai chocolate” could be considered clearly descriptive because it tells potential purchasers what the chocolate is, and describes a property commonly associated with it, namely its location of origin.[15] Canadian trademark law also does not allow applicants to register the name of the ware itself, and “Dubai chocolate” could be argued to be the name of the specific type of chocolate bar, similar to the term “dark chocolate” or “milk chocolate.”[16] Thus, I think it is unlikely that the term Dubai chocolate would be considered a valid trademark under Canadian law.

While the intellectual property debate over the term “Dubai chocolate” may not play out in Canada, it is interesting to consider what it would look like under Canadian law. Hopefully you can all enjoy some chocolate over this long weekend, even if it is not Dubai chocolate!

[1] https://www.dw.com/en/dubai-chocolate-as-a-tasty-trend-goes-viral-who-owns-the-trademark/a-70987768

[2] https://ip.fasken.com/are-recipes-protected-by-copyright-law/

[3] https://ip.fasken.com/are-recipes-protected-by-copyright-law/

[4] Trademarks Act RSC, 1985 c T-13, s 7.

[5] Ciba-Geigy Canada Ltd v Apotex Inc, [1992] 3 SCR 120, 143 NR 241.

[6] Orkin Exterminating Co Inc v Pestco of Canada Ltd, 1985 CanLII 157 (ON CA).

[7] Sadhu Singh Hamdard Trust v Navsun Holdings Ltd, 2016 FCA 69.

[8] Reckitt & Colman Products Ltd v Borden Inc, [1990] All ER 873.

[9] https://www.dw.com/en/dubai-chocolate-must-come-from-dubai-german-court-rules/a-71290421

[10] Institut national des appelations d’origine des vins… v. Andres Wines Ltd, (1987) 60 OR (2d) 316 aff’d Ont. CA (1990) 74 OR (2d) 203.

[11] Spalding v Gamage, (1915) 84 LJ Ch 449.

[12] Orkin Exterminating Co Inc. v Pestco of Canada Ltd, 1985 CanLII 157 (ON CA).

[13] https://ised-isde.canada.ca/cipo/trademark-search/srch?payload=%257B%2522domIntlFilter%2522%253A%25221%2522%252C%2522searchfield1%2522%253A%2522all%2522%252C%2522textfield1%2522%253A%2522%255C%2522dubai%2520chocolate%255C%2522%2522%252C%2522display%2522%253A%2522list%2522%252C%2522maxReturn%2522%253A%2522500%2522%252C%2522nicetextfield1%2522%253Anull%252C%2522cipotextfield1%2522%253Anull%257D

[14] Trademarks Act RSC, 1985 c T-13, s 12.

[15] Unilever Canada Inc v Superior Quality Foods Inc, (2007), 62 CPR (4th) 74, [2007] TMOB No 66.

[16] General Foods Ltd v Carnation Co, (1978), 45 CPR (2d) 282 (TMOB).

Copyright & Social Media

Copyright & Social Media Communications Law

Communications Law